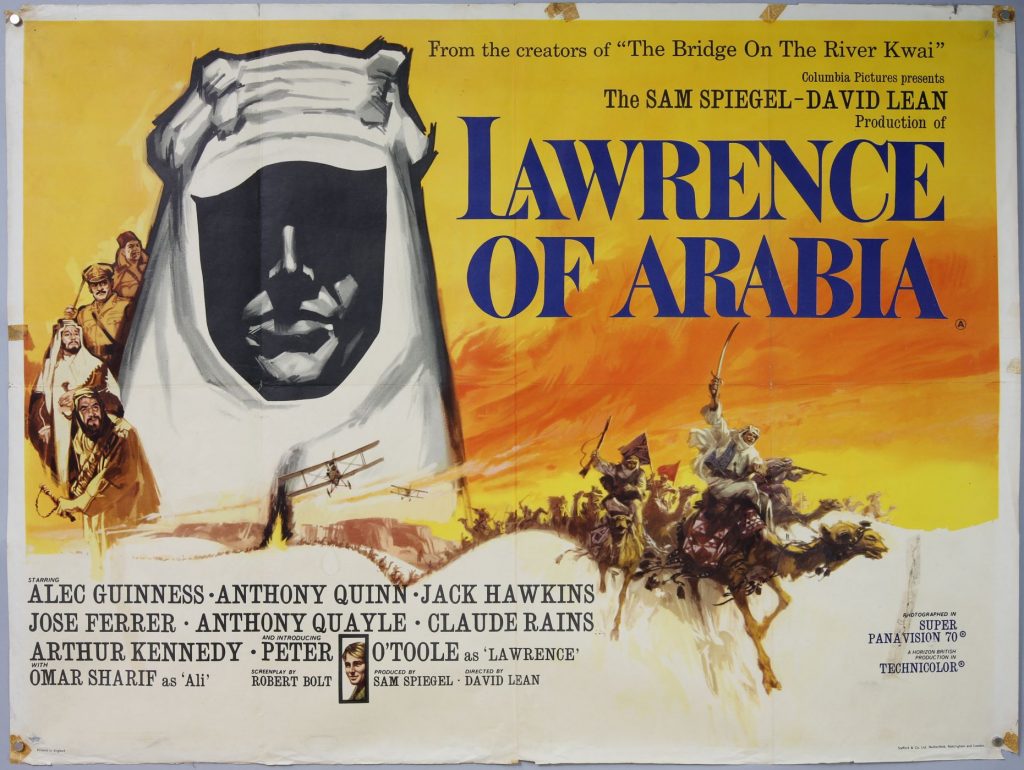

Lawrence of Arabia (1962)

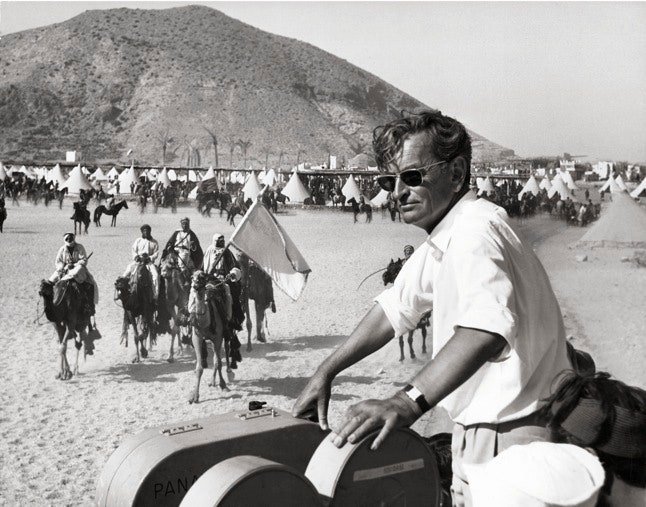

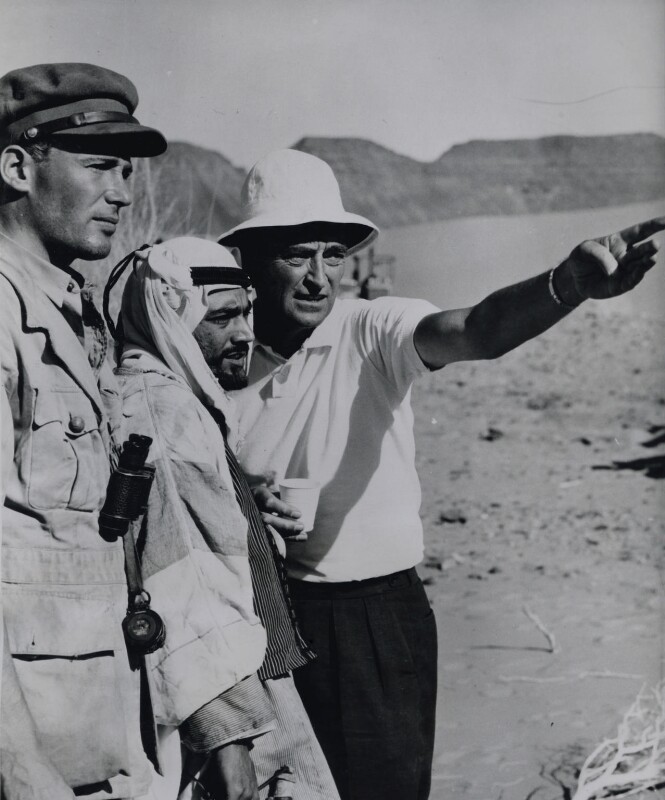

Dir: David Lean

Stars: Peter O’Toole, Alec Guiness, Omar Shariff, Jack Hawkins, Anthony Quinn, Claude Raines, Anthony Quayle and Arthur Kennedy

We say “experience” a lot these days in the marketing of films. You often hear phrases like “epic” and “sprawling” and “game changer” and “a truly cinematic experience.” Sure, you might argue that Lawrence is a film that is past its prime, a tribute to the old style of films. And, you’d have cause to say that, what with its nearly four hour run time, intermission and overture played before the first and second half of the film – not to mention a cast entirely composed of men. But, there is something to be said about a piece of art being showcased in the space it was intended. Would you want to see some of the work at the Chicago Art Institute in a rotting old warehouse? Or better yet, for the purposes of this blog entry – imagine taking your favorite painting, but hanging it in your own living room?

Obviously, there’s the option to see Lawrence at home on one of the streaming services or hopefully off your Blu-Ray – you still have one of those, right? However, my feeling is that some movies are better than others. Some really deserve their listing among the greats. Whether that’s on an official, industry list like the AFI’s, a collection of critics or a personal one is irrelevant. Some films are meant to be seen in a cinema setting because they truly emote that “film experience” tag line, and our viewing of them evolves as we watch with others in the dark theater. The elite in any artistic endeavor deserve a proper presentation. And for me, Lawrence of Arabia is the very textbook definition of “movie experience.” So again, if you have never seen it, and you want to watch it at home – by all means do so! But, I’m humbly recommending that if it’s playing at a cineplex once things turn around and we start going to theaters again… grab the opportunity.

This film is in my top ten of all time not because I think it should be, but because it’s got a lot of personal connections to my upbringing. I’m named after the man for one. And, one of the photographs of Lawrence from his adventures in the desert hangs in my Dad’s home office. Mr. Lawrence’s gaze would find me often as I grew up. When I was around kindergarten age, my Dad loaded me into his car and drove me downtown Cincinnati because Lawrence was playing there on the big screen. Now, I honestly can’t remember if I saw this for my first movie experience, or whether it was E.T. Regardless of which one came first, I remember Lawrence, even in that first viewing. I’m not going to claim to have followed everything or that I really paid attention throughout. I mean, there was soda, and popcorn, and raisinetes to enjoy. But, it left an impression. Who was that heroic figure in the white robes? Why are they riding camels… into the desert? How can I listen to this music some more?

There are sequences that I remember that change with each viewing of the film. The first time, I remember specifically the action. Lawrence blowing up trains and attacking the Turks with the Arab Army. Then there’s the crossing of the desert to Aqaba. When I was young, I remember the triumphant attack on the Turkish garrison. It’s a pretty sweeping, epic scene with a cast of thousands and action unfolding on camels and horseback across that glorious 70mm screen. When I saw it most recently, the contemplation that Lawrence puts into the Aqaba attack, the potential to attack from behind – that was what grabbed me. The point is, Lawrence is one of those rare movies that ages like fine wine. You watch it, you have fond memories of it, you have an opportunity to see it again – and in this latest viewing, it shows you something new entirely. Many of my favorite films share this aspect, of presenting me with a new perspective or unveiling a storytelling technique not previously noticed.

Having viewed the film numerous times since the original trip with Dad, I think when you really peel the onion of Lawrence, the question the film presents to us the viewer in light of Lawrence’s personality and adventures is, “Who are you?” In some scenes, he is a true, classic Crusader, who wants to help a people in their quest for freedom. In other sequences, he’s an egotistical maniac. In still others, this great man who put quite a stamp on the 20th century… just wants to be left alone. There’s a certain sequence that will help me with what I mean by the “Who are you?” question. When T.E. Lawrence has returned across the Sinai desert and reaches the Suez Canal, he’s catatonic from his recent experiences. The man looks half dead. One of his Arab guides tosses water in his face to wake him up. They climb a small hill to see the Canal, and the guide waves down a British officer on a motorbike on the opposite side. To conclude the scene, the officer yells at Lawrence, “Who.. are… you?”

Earlier in the same scene Lawrence insists on walking in the desert as his guide rides the camel. He’s walking because he’s punishing himself. There were three of them that started the trek across Sinai, but the other guide has just died in a spot of quicksand. Lawrence is blaming himself – something he does on screen in this film, and was a lingering trait of his personality that he wrestled with all his life. The surviving guide basically forces Lawrence to understand that his walking “serves no purpose” and that there’s plenty of room on the beast for both of them. In this scene, Lawrence acquiesces, although he doesn’t always when it comes to berating himself.

From the technical aspects of the scene to O’Toole’s performance, the sequence might not be high on your list of memorable scenes from the movie. However, it explains a lot about the man. I’m probably skewed and admit I might be overthinking some of the smaller scenes like this one. But, I actually finished reading one of Lawrence’s biographies earlier this month, and to say that he was a fascinating character is very appropriate. This film focuses on about two years of the man’s life, which ended as depicted in the opening scene. But, think about that: the film is nearly four hours long, and we’re only scratching the surface of who and what “Lawrence of Arabia” meant to history. This fact brings us back to the “Who are you?” question. Can you imagine the fame and focus on a man that did what he did? Having read the biography I mentioned (A Prince of Our Disorder by John E. Mack, in case you’re interested), you can understand better Lawrence’s desire to be left out of Allenby’s “big push” or relieved to hear he’s got his own cabin for the boat ride home. In sum on this point, I guess one of the things that the film does is make you eager to learn more about its subject.

The biography filled in a lot of blanks. One of them that stood out was that Lawrence grew up learning all he could about the Crusades. He was always an avid fan of poetry. In other words, much like our recent entry on Patton, it’s like Lawrence was born of another time. From early years, Lawrence felt in his bones that he was destined for great things. So, like the elite films, the man himself was elite in his thinking and beliefs. This 1962 film directed by David Lean focuses specifically about Lawrence’s “Seven Pillars of Wisdom,” or the abridged and more digestible “Revolt in the Desert” as it has come to be known. While most of us probably understand most about World War I as it pertained to the European theater, Lawrence and his British comrades were stationed in the Arabian theater. The Ottomon Empire had ruled this section of the world for centuries. Essentially, Lawrence is the story of how one small statured, soft spoken British man was able to unite the tribes of Arabia to bring down this seemingly unbeatable enemy. For perspective, the General that Lawrence ends up reporting and fighting for, Allenby – this man liberated Jerusalem in 1918, which had been Turkish territory for four hundred years.

Getting back to the film itself, it’s definitely one that fires on all cylinders – from the music to the acting to the technical phenomenon of such a grand cast and crew working in the middle of desert locations to those memorable scenes. The direction by David Lean has been documented and described by reviewers and cinema academics much more knowledgeable than myself. The same can be said for Peter O’Toole’s portrayal of Lawrence. The TCM intro I saw of the movie recently advised that this was O’Toole’s fourth role in a movie! As far as I’m concerned, it’s one of those so grand in its effort that the actor would never have had to play anything else – and he’d still be in the “best ever” discussion. So, while I don’t feel like I can offer that much in way of a “new perspective,” what I will say is that at nearly four hours in length, I am always impressed how there is not a segment or individual scene that I can think should have been cut. There is not a character that we could have done without. Perhaps the cinematography by Freddie Young (who incidentally also did Lean’s pictures Doctor Zhivago and Ryan’s Daughter) is reason enough to see Lawrence on the big screen. Or, hearing Maurice Jarre’s sweeping score with its Overture and all. The sequences I’ve done my best to describe are the ones that effected me. But what about the fantastic effect of the match-on-action, when Lawrence blows out the match to reveal the dawn in the desert?

I’m also sure to admit that in parts, the film is naturally dated. But to Lean’s credit, Lawrence on the whole holds up even by today’s audience’s standards. I know this because the last time I saw this epic in theaters was with a good pal of mine who had never seen it on the big screen. There we sat in the Aero Theater in Santa Monica, CA a few Memorial Day weekends ago. The film started and it’s only the overture playing for three minutes without any images. A couple minutes in, my friend K.D. asked me, “What the hell’s going on? Is there something wrong with the screen?” We then talked about old movies and how a lot of the epics had an overture and another musical block during the intermission.

The encouraging thing to me about the Aero viewing was the fact that no seat in the theater was empty. It was a sunny, pleasant Memorial Day weekend holiday – and yet, the theater was packed! The audience laughed at some of the dated moments and curious dialogue, which is understandable. What I mean is, there’s a lot that has happened in the Middle East since this story unfolded in history and was subsequently filmed in 1962. But no one talked through Lawrence. Nobody texted. We were all having… a cinematic experience. And so, since today is my birthday and I am actually named after Lawrence, let me encourage you to add Arabia to your bucket list if you haven’t had the opportunity just yet. You won’t regret it.